Leaving Lizards

It’s been over a month since I last saw a lizard. I miss them more than I thought I would.

For the first three decades of my life, I saw lizards — specifically, brown anoles (Anolis sagrei) — each and every day. They are ubiquitous in Florida, as common a bit of fauna as you're likely to find in the Sunshine State. No matter where I went, from country towns to city centers, lizards were everywhere.

About two to five inches long, colored various shades of brown, and frequently with stripes, patterns, or even crests running down their backs, anoles venture out onto sidewalks to hunt insects or bask in beams of light. Alert to approaching footfalls, they quickly run for cover in nearby foliage. To walk in my home state is to see a cascading pattern of skittering reptiles ahead, each taking its cue to flee in turn.

When dried leaves cover the ground, the lizards’ sprawling toes drum on their crunchy surface as they escape into the underbrush. It’s noisy, like someone playing with a giant ball of cellophane. It sounds like home to me. Anoles are otherwise stoic creatures, silent and leery, readable only through their movements.

I’ve seen lizards do pushups. I’ve seen them flirt. I’ve seen a lady lizard reject a male suitor. I’ve seen them fight and defend themselves. Catch a bug and eat it. I’ve even seen them knock (lizard-skin) boots, if you catch my drift. All in public! They just do it in the park, every single thing. Not far from people, either.

That’s what I miss the most, I think: watching lizards. Noticing what’s going on in their little lives. I’ve seen lizard moms and lizard eggs, baby lizards (they are so cute it’s unreal), lizards in their prime, grizzled lizard elders, and lizards that were dead. Few other animals show you their life cycle so completely — and it’s not just happening out in the woods. On every front porch in Florida, lizards have lived entire lifetimes in obscurity.

Catching lizards was a childhood pastime. The kids I grew up with were captivated by these everyday dinosaurs that dwelled within the ensemble of tangled hedges and dense border grass that defined that particular Floridian landscaping style. Their frenzied running ignited in us a sort of predator instinct. We were perfect adversaries; the lizards were swift and agile, but just slow enough to be caught, and we were clumsy, distracted kids who missed about three of every four lizards we chased. Either side could come out on top.

To catch them required precise timing and every bit of our still-developing hand-eye coordination. We dove headfirst into the grass, our grubby grabbers cupped over our quarry, which writhed under our palms. Lizard snouts prodded the tiniest gaps between our fingers, seeking a chance to slither through and away.

Occasionally, we’d catch only a wriggling tail, detached as a diversion while the lizard made its getaway under the grass. The tails themselves were a rich subject of study for our band of backyard naturalists. There was no real body horror about them. They fell off cleanly; as easily as a poorly tied sneaker during an intense bout of kickball.

Separated from the lizard’s body, the tail remained full of life, contorting like the worms above ground after rain. On an open palm or down on the driveway, the severed tail performed its peculiar choreography until its limited, half-hour run concluded. Elsewhere, the lizard began regeneration immediately, a new tail fully in place within 60 days. All over the neighborhood, we saw lizards with tails in various stages of regrowth. A fully regenerated tail was never quite the same color as the rest of the lizard, and the oldest, largest individuals bore scars from multiple cycles of loss and recovery.

The odds of a successful capture were better when we spotted a lizard perched proudly on the trunk of a narrow tree, nearly invisible to animal predators and ambivalent adults; but to the trained eye of grade school poachers, easy pickings. With a slow approach, some careful mental calculus, and a fast strike, the wriggling lizard would be pinned — gently, but insistently — between our palm and the bark. After a moment, we’d skillfully flip the anole off the tree and into our hand for inspection.

Cuban anoles often took to trees and the tops of rocks during mating season. The males proudly flashed their orange-red dewlaps, dexterous flaps of brightly colored neck skin that attracted mates and intimidated competitors. That flash of eye-catching color was enough to attract our attention as well; otherwise, we, too, might have overlooked the well-camouflaged lizard.

We’d comb a planned circuit of proven hunting grounds, working hard until we had a lizard in our clutches…and that was usually about as far as we’d thought things through. But our curiosity demanded that we postpone release, so we arranged accommodations.

We’d craft terrariums: five-gallon buckets, thoughtfully appointed. A bed of dirt and sand at the bottom was garnished with shoots of grass (roots still attached, hopeful that a small lawn would grow) and accompanied by the finest selections of sticks and rocks for our guests’ engagement. Occasionally, our parents contributed store-bought plastic terrariums, in which we replicated our habitat formula. At times, we’d have two or three going at once.

A few lizards would be detained in these enclosures each day, and we’d watch them from above: how they interacted with the environment, with one another, and with the insectoid supper that had emerged from fistfuls of dirt. It was a makeshift menagerie and endless fun. In those days, we didn’t know what the internet was and we didn’t care. How irresistibly quaint. The halcyon late 90s; nostalgia 100 proof.

Eventually, the street lights would come on and we’d head inside for dinner and bed, leaving the terrariums occupied overnight. Returning in the morning, many of our captive lizards would be missing, presumed escaped. I took pity on any that remained and bestowed amnesty, lifting them out of confinement. I deposited them carefully onto the lawn where they’d flee, never looking back.

The anoles had three means of defense against us. First, their surprisingly powerful squirms made them difficult to hold on to. I never considered whether some of the more ardent fighters may have been previous terrarium guests who hated my guts, but that’s a thought-provoking hypothesis.

If squirming didn’t work, they pooped, a classic survival response in the animal kingdom. Gross and grimace-inducing, but manageable with no more than a leaf to wipe it away.

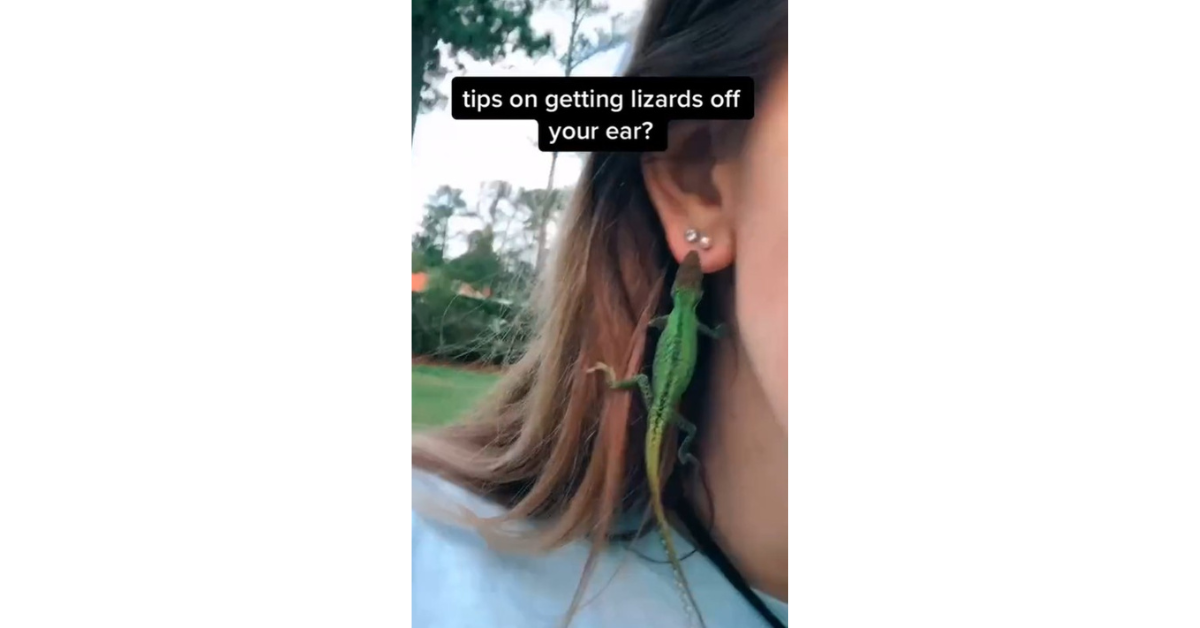

With no other recourse, the lizards bit our fingers. Lacking substantial teeth, their bite didn’t hurt, really, but it was tight and persistent, like being squeezed between two dull fingernails. As a result, it could be used for fun. A lizard lifted to an earlobe would bite down and hold, dangling there even after it was released. Voila! A lizard earring.

It’s not clear to me if we were taught these games by grown ups, discovered them for ourselves, or appropriated them through the sort of cultural exchange between neighborhoods that occurs when kids of similar ages but different ZIP codes meet at school, church, or public parks. What I do know is that I’ve met many adults who share the same fond memories of catching lizards and the joy of hanging them from your ears, even if they lack my lifelong fixation.

Lizard life was cheap, I’m sad to say. Their freedom and safety was not only not a priority to us, but barely registered. Their release was more a result of kids losing interest in a game than any moral conviction. We had no concept of animal cruelty or its potential consequences.

Looking back as an adult, I feel a bit bad about how my little friends and I treated lizards. I recall casualties; lizards suffered and died in our captivity, not through animus but rather neglect. It turns out that kids who can barely keep their own shoes tied make poor zookeepers.

It’s been over a decade since I caught a lizard. I worry that, if I tried today, I might hurt them (or myself, to be frank). I still appreciate their unique charm and they are among my favorite animals. Today, I am content to observe lizards from a distance.

In my day-to-day life — not even, like, trying, just…existing in Florida — I’ve observed that brown anoles exist in staggering numbers and fill an important ecological niche. That makes it hard for me to imagine that there was a time, not even 100 years ago, when no population of brown anoles existed outside of Cuba and the Bahamas.

At some point in the early 20th century, a lounge of Cuban anoles (that’s what a group of lizards is called. Look it up) boarded ships bound for the Florida coast and disembarked into a land of opportunity.

Brown anoles might be the most successful invasive species on the planet. Not only have they become the most abundant species of lizard in Florida, but populations are growing in bordering states like Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana — not to mention more distant places like Mexico and Hawaii. The latter two reached, once more, by stowing away on ships. What can I say? The little buggers love the high seas.

Brown anoles moved to Florida with no intention of retiring. They quickly outcompeted their green cousins (A. carolinenis), whose populations diminished and became more arboreal, their vibrant chartreuse coloring affording invisibility among the canopy. By 1940, brown anoles had claimed almost exclusive dominion over the low branches, tree trunks, and sidewalks, all rich with the small insects they eat.

They were so mundane that to see another kind of lizard felt miraculous. There were a few, we knew; we’d seen them, in fleeting moments. We knew them mostly in relation to what they were not. A lizard that was standing with a weird posture or in a weird place, or one that physically differed from the brown anoles in some fundamental way, first elicited absentminded curiosity, then adrenaline-pumping fascination. Something new! Different! Here, in our space! Without leaving our cul-de-sac, our world had grown bigger. It’s a feeling I still nurture in myself.

A green anole, having ventured down from its home high above our heads to be a petty inconvenience on the cousins who had forced him from his territory, had a certain gravitas. It failed to blend in, as if issuing a challenge. We took up the gauntlet gladly. Brown anoles were easy to capture, but green anoles were faster and seemingly smarter, more cautious. Success was rare and failure expected.

The geckos (Hemidactylus mabouia) that came out after dark were a bit more common, but also more alien. They had bulging, reflective eyes and their skin was smooth, not scaly. They were a translucent, whitish yellow that reminded me of the glow-in-the-dark plastic stars I’d stuck to the ceiling in my room. They returned, night after night, slipping from some impossibly narrow crack to claim the wall above the front porch light. There, they opportunistically snatched up the flying insects orbiting the sconce.

Geckos were even faster than green anoles and great at escape. When pinned, they would deftly slip out from beneath my hand and climb the wall in a flash. When I did manage to hold onto one — probably during a chance encounter with the nocturnal lizard during daylight hours, when it would rather be asleep — its see-through skin fascinated me. Once, I caught a pregnant female and watched a pair of round eggs bob within her belly for a few moments before setting her free.

I never caught an eastern fence lizard (Sceloporus undulatus), but I remember seeing a few confidently standing atop the sort of wooden privacy fence that every third neighbor had. Their physiology made them truly remarkable. They had spiky, textured skin, stocky builds, frowny faces, and a bright blue belly. These lizards looked like nothing else in Florida, more resembling the bearded dragons at the pet store. They occupied yet another tier of speed and agility, surpassing the lizards I was used to. Comically fast, like the cartoon Roadrunner, they vanished at the merest approach.

Seeing an eastern fence lizard was a good omen in my childhood — an unexpected surprise that injected wonder and curiosity into my day.

The recess field at my elementary school seemed to go on forever. Beyond the pavement where kids shot hoops and played four square, beyond the playground and the shaded picnic table where teachers sat, supervising, was our very own sundrenched Serengeti. My friends and I were uninterested in the ball games but craved exploration, so we ventured out into the open plain, massive brown dragonflies zipping through the air all around us. The heat from the sun intensified overhead as noon approached.

The property line of the school was marked by a tall chain link fence. Beyond that was the woods. Lizards would wander out into the grass to hunt insects and bask, undisturbed all morning until our tiny Reeboks trudged by. They ran for the woods and we gave chase, struggling to catch one before the opportunity passed us by. Such was my recess for who knows how many days of second grade.

One day in that field, I spotted something different alongside the familiar brown anoles that sprinted over the grass: a flash of blue. This unknown creature attracted my full attention, moving much quicker than anything I’d pursued before. It was hard to get a good look at it. I ran after it until I crashed into the fence. My fingers gripped the chain links like a yearning inmate as I watched lizards disappear into the underbrush all around; and directly in my gaze, slithering over a bed of leaves, was my first skink (Eumeces Plestiodon inexpectatus).

Its body was dark — nearly black — and adorned with what my young mind could only perceive as zebra stripes. Its scales reflected light, giving it an attractive shine. Most intriguing of all was its baby-blue tail. This lizard was unlike any I’d ever seen. Its striking combination of odd features gave it a sort of platypusian singularity. Inexpectatus, indeed.

I had to catch it.

I hunted this magnetic creature for what felt like ages. I felt the same way someone with a hot lead on a unicorn might feel. Each day, at the beginning of recess, I would make a beeline to the field and rouse the lizards dozing in the grass. I ignored the brown ones — plenty of those at home. Instead, I scanned the fleeing reptiles for any hint of blue. I was Ahab then and the skink was my terrestrial white whale.

I was never fast enough. Again and again, I failed, once more weaving my fingers anxiously through the metal fence as I watched the skink vanish into the woods, having once more outmaneuvered me with indifferent ease. Oh well — tomorrow always promises another opportunity.

Chasing the skink was my herculean labor — the stuff of legends. It was also a Sisyphean task — doomed to fail. The skink was faster than I would ever be. It could go places I could not follow. It felt ethereal — truly mythical.

I felt like I was chasing a phantom. It didn’t help that I lacked adequate words to explain my enthusiasm. My description of the skink was met with skepticism by kids and adults alike, as if anyone would make up a shiny, half-zebra lizard with a blue tail! I eventually stopped talking about it. I knew it was there, and I had to see it up close — but I kept that to myself.

Eventually, summer break arrived and my final opportunity came and went without success or even a realization that that’s what it had been. It was the same experience: leaning into the fence, casting longing looks at the lizard who would forever be my better.

When I returned to school for third grade, my class went to recess in another field. The new schoolyard did not border the woods, but instead the parking area for the pickup line (famously skink-free). We moved on to more grown-up games than chasing lizards; for example, freeze tag. There would be no more chances to catch that skink and eventually it faded from obsession to memorable tidbit. The saga had ended. I entered a new chapter of childhood and life went on.

I lived in Florida until my thirty-third year. I never saw another southern five-lined skink.

Knowing that I was born and raised in Florida, it may surprise you that I have only visited Miami once. Florida is huge, you see, and getting to Miami from Tampa really sucks.

Such a trip demands a special occasion, so my wife and I traveled there for my birthday two years ago. It was August, and the heat and humidity were approaching their annual peak. We stayed in the city, a short walk from Biscayne Bay, and spent our first day fully exploring the Frost Museum of Science.

We left Frost around 5:30, as the museum began to wind down toward closing time. The sun was less brutal then, sinking lower over the skyline, but its effects on the air — more sauna than oven — lingered. This was our best chance to walk the waterfront, so we stayed outside and explored.

Not far from the Frost Museum and in the shadow of its neighbor, the Perez Art Museum, is Maurice Ferre Park. There is a paved courtyard on its northeastern edge that overlooks the bay, and that’s where we started our walk. Palm trees swayed overhead and the rims of the concrete planters around the palms served as benches for the tourists and locals gathered there. We had been in this part of the park for just a moment when I had an experience straight from my childhood.

A flash of brown in the corner of my eye caught my attention, and I saw a lizard on the pavement a few feet away. Like before, I identified it by what it was not. It looked very similar to a brown anole at first glance, but stood up taller, had rounder features, and held a curly-q tail high above its back. Scanning the courtyard, I saw more of them, running here and there, exactly like the brown anoles in Tampa. Every little lizard in the area was this species — I didn’t spot a single brown anole the whole trip (I learned later that this species preyed on them). This was my first experience with northern curly-tailed lizards (Leiocephalus carinatus).

About 18 months later, my wife and I began to make our rounds of the places we’d miss the most when we left Florida in April 2025. Dunedin was a stop on our farewell tour, a coastal town near Clearwater. The most scenic drive between the two is perhaps Edgewater Drive, a two-lane road that runs between shady blocks of homes and the sea. We parked along it and went on a walk through the neighborhood, imagining what it would be like to live in each house, appreciating the details of each lot. We felt nostalgic for Florida in those moments; we called it our graduation goggles.

Then I noticed an additional detail about the neighborhood. In at first one garden, then more, I was shocked to see the same curly-tailed lizards I’d encountered in Miami. After seeing them there, I’d done some research: Curly-tailed lizards were also invasive transplants from the Caribbean islands, intentionally introduced to South Florida around 1950 as part of a pest control initiative. They supposedly had a limited range, yet here they were, apparently having expanded their habitat nearly 300 miles.

It occurred to me that history was repeating. Like the brown anoles, these curly-tails had been carried by humans to fertile new grounds. Would they outcompete the brown anoles (or just eat them) and drive them away, like the brown anoles had done to the green? Would future generations of Tampa Bay residents walk outside to yards full of curly-tailed lizards? Would seeing a brown anole be as unexpected to them as seeing a green anole had been to me?

Whatever the future holds for Floridian lizardom, I won’t be around to see the drama unfold. I’ll be far away, exploring a new territory of my own. Perhaps this is one reason I relate to the lizards I grew up with; I’ve longed to follow in their footsteps, going beyond the borders of my old habitat and proving that I can thrive there.

I imagine that somewhere in Tampa Bay this summer, a curious kid will see the first curly-tail arrive in their neighborhood. Maybe they’ll try to catch it, fall short, and anxiously await the next opportunity. I hope the lizards give them the same spark of wonder that they gave me all those years ago. I hope that, over time, the lizards begin to remind them of home.

I knew that moving to Minnesota would have its costs. For one thing, I was leaving behind family, friends, familiar neighborhoods, and favorite restaurants. I was trading a year-round warm climate for four seasons, including notorious, freezing winters. As the day approached, I thought of less obvious concerns. The flora and fauna around me would also change, I realized, and I began to imagine how that would feel.

The endless scrambling of lizards had been a consistent throughline in my life. They were all around me, constantly in view. How would leaving them affect me? Family and friends could be reached easily through technology and new places would become familiar over time, but I wondered how such a fundamental change in my environment might impact my mood.

I was relieved to discover that there were three native lizard species in Minnesota, including a close relative of my old nemesis, the five-lined skink (E. fasciatus). In the Twin Cities, I would be most likely to find the northern prairie skink (E. septentrionalis).

Okay, cool, I thought. I can work with that. Although I knew from experience that skinks were elusive, I failed to fully comprehend the implications.

Located within the Mississippi River National Recreation Area, Saint Paul brilliantly integrates city and nature. Downtown is full of green spaces and shoreline, and the suburbs are liberally peppered with regional parks that offer pleasant woodland hikes. On my daily walks, I follow paths that, back in Florida, would be crawling with gregarious lizards; yet here, there are none. I travel miles on foot along tree-lined trails, but hear nothing rustling in the brush. I haven’t seen a single skink since I arrived, and I don’t know how long it will be until I do.

Lizards were everywhere in my rural home town, but they existed in equal numbers within downtown Tampa, too, flourishing just as well between concrete high-rises as they did in my mom’s flower bed. No matter my address, lizards were my constant neighbors. Their absence signals that I have once again started a new chapter.

I have many, many reasons I’m happy to have moved to Minnesota. It was a quality of life improvement that will pay dividends in the years to come and I believe that it won’t be long until it feels like home. But for now, the paucity of lizards is a daily reminder that I’m 1200 miles away from what I knew.

As in childhood, seeing a blue-tailed skink might be a good omen: a physical reminder that parts of my old world are still with me here. I picture that first Minnesota lizard as an avatar of hospitality. Its appearance will anchor me here. It will urge me, once more, to fully explore my new environment in search of overlooked wonders.

So I walk in the woods with my eyes and ears open. I peer into thickets. I turn over rocks. I search daily for that small, remarkable encounter that will let me know I’m home.